Mastering Gradient Descent: The Art of Feature vs. Target Scaling

Welcome back to the lab. 🧪

Gradient Descent is the backbone of modern machine learning optimization. However, as I discovered in this latest experiment, its performance is incredibly sensitive to the scale of your data.

In my previous projects, I relied on libraries to handle the heavy lifting. This time, I built a Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) model from scratch using batch Gradient Descent to answer a specific question: Should we scale just the inputs, or the targets as well?

Here is my log of the experiment.

1. The Engine: Building the Regressor

Before running the tests, I implemented the math manually. The prediction function $\hat{y}$ for a given input vector is defined as:

To train this, I used the Mean Squared Error (MSE) cost function. It’s perfect for Gradient Descent because it is convex and differentiable, meaning we can easily find the bottom of the “error valley”.

The weights were updated iteratively using the gradients:

2. The Setup

I used a student performance dataset ($n=10,000$). To evaluate the results fairly, I looked at the MSE for the loss, but I also calculated the Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) to get a percentage-based accuracy score.

I ran three distinct experiments to see how scaling affected convergence.

3. Experiment I: The “Hybrid” Approach (Winner) 🏆

Configuration:

- Inputs (X): Normalized to a standard range.

- Targets (y): Left in their natural scale (0-100 exam scores).

The Result: This configuration was the clear winner. The model converged within 2,000 epochs with a MAPE of 3.73%.

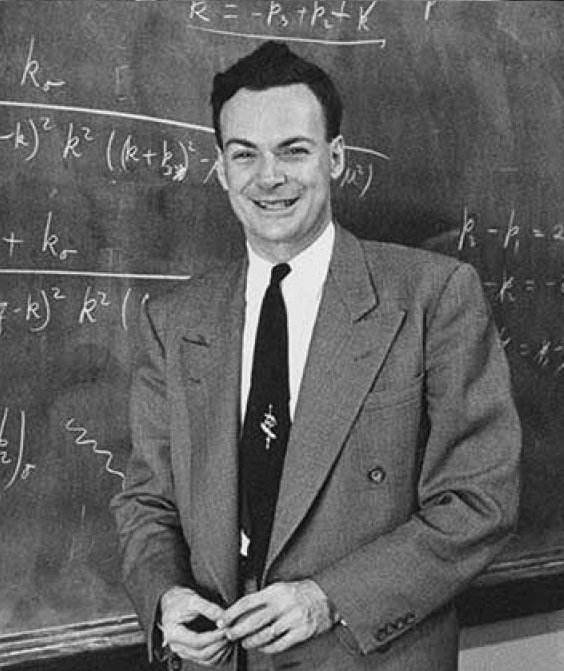

As you can see in the plot below, the predictions (blue dots) tightly follow the ideal red diagonal line, proving the model learned the distribution perfectly.

(Figure 1: High accuracy fit with $R^2 \approx 0.99$)

(Figure 1: High accuracy fit with $R^2 \approx 0.99$)

4. Experiment II: The “Raw Data” Chaos

Configuration:

- Inputs (X): Unnormalized (Raw).

- Targets (y): Unnormalized (Raw).

The Result:

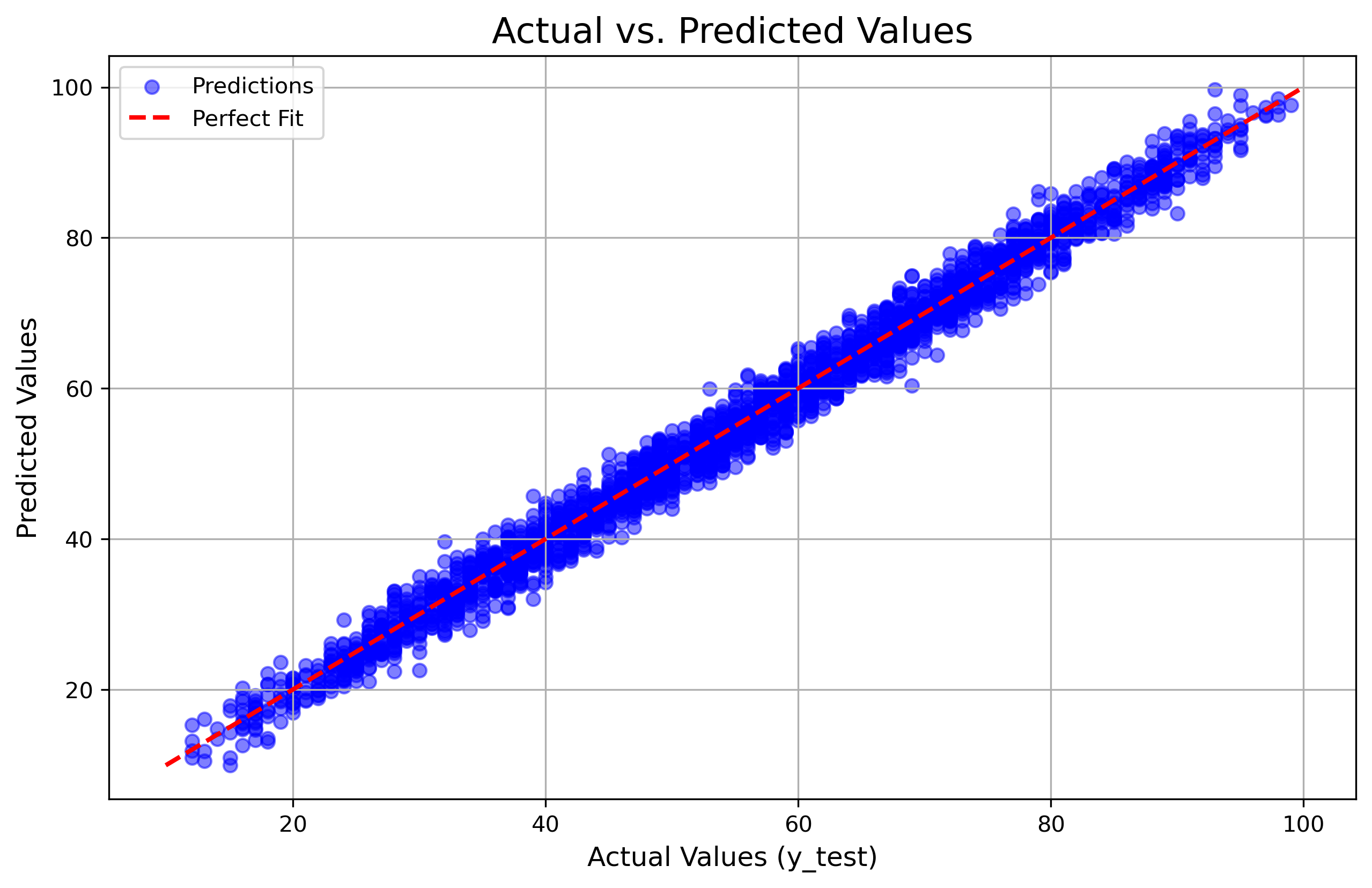

This was a disaster. The unnormalized inputs created an elongated loss landscape. When I used a standard learning rate ($\alpha=0.01$), I hit an Overflow error—Exploding Gradients.

I had to reduce the learning rate to a tiny $0.0001$ just to get it to run, and even then, the performance degraded significantly (MAPE 11.52%). The scatter plot showed much higher variance (noise) compared to Experiment I.

5. Experiment III: The “Over-Normalization” Trap

Configuration:

- Inputs (X): Normalized [0, 1].

- Targets (y): Normalized [0, 1].

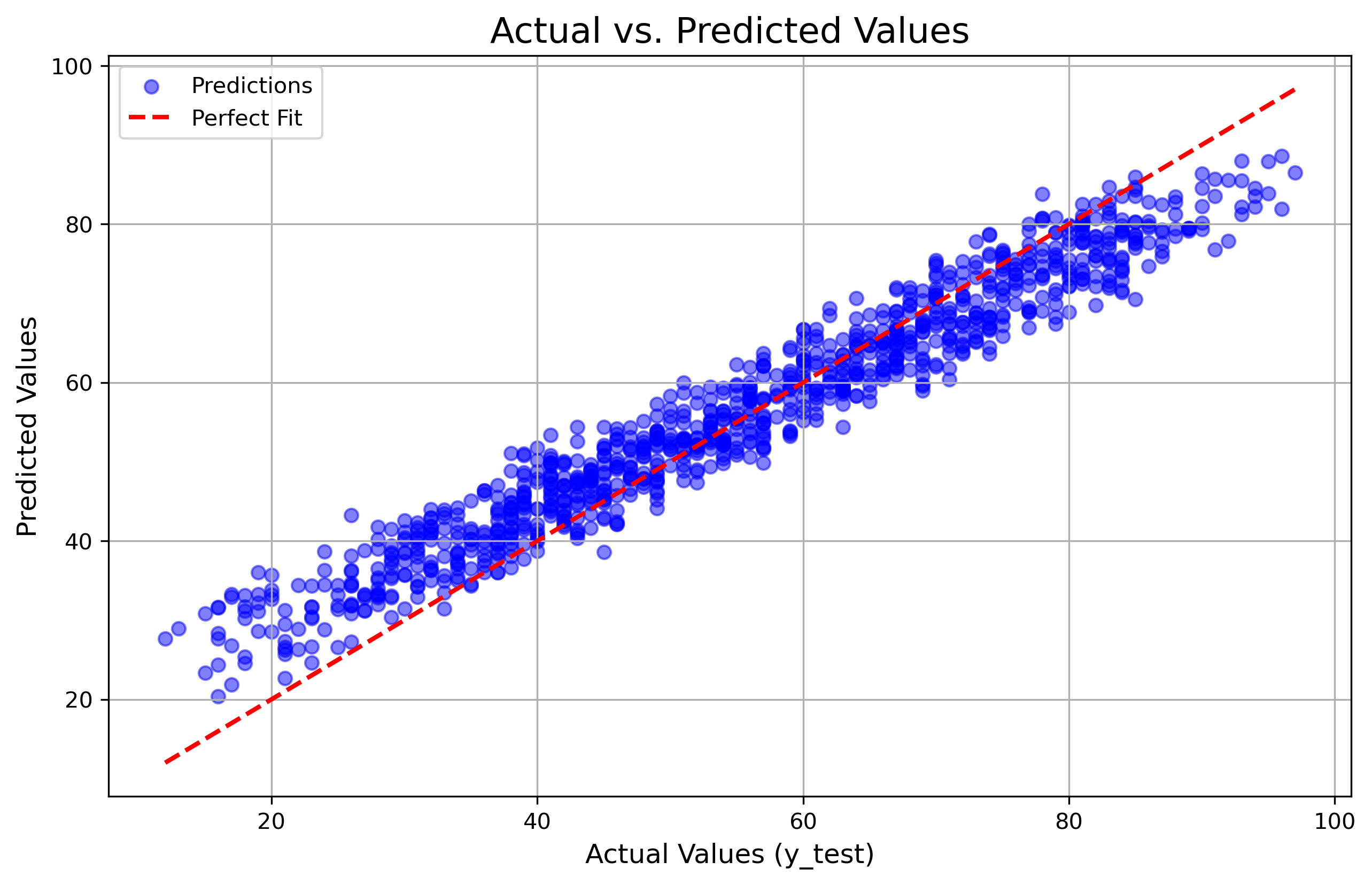

The Result: This was the most surprising finding. I assumed scaling everything would be better, but the model stopped learning entirely.

This led to the Vanishing Gradient problem. Because the target values were so small (< 1), the calculated gradients approached zero. The weights didn’t update significantly, and the model got stuck predicting the mean of the dataset for every single student.

(Figure 3: The “Flatline.” The model fails to learn the slope entirely.)

(Figure 3: The “Flatline.” The model fails to learn the slope entirely.)

Conclusion

This experiment provided empirical evidence of an asymmetry in Gradient Descent.

- Scale your inputs: It is non-negotiable for numerical stability and preventing exploding gradients.

- Don’t scale your targets (usually): For regression tasks with bounded outputs, scaling targets to [0, 1] can compress gradients too much, trapping the model.

The optimal configuration is a hybrid one: Normalized Inputs + Natural Scale Targets. This achieved the best balance of stability and precision (3.73% error).

Next time, I’ll be looking into how different weight initialization strategies might help solve some of these issues from the start!